So where do you start? How can you at least get to where you can guesstimate semi close? If we break it down to the science of how much wind effects bullet in set conditions, we can then apply the "knowns" of how much the bullet drifts in set conditions, and then all we have to do is "guess" at what the current conditions are. So, the first thing we should do is take a look at some wind charts. Once we are familiar with the wind charts for our caliber, then we can move into estimating wind, and estimating the effects it has on our bullets flight. So, lets move on.

Wind Charts

Most all wind charts provided in ammunition manufacturers catalogs are set at a direct 10mph crosswind. This generally will work find for us. The problem is finding charts that go out to long ranges. Most only go to 300 or maybe 500 yards. I, being US Army trained, like to look at things in meters, not yards, which makes it harder for me to get data. A good ballistics software package can help here and is probably what you will need to use to get detailed charts in whatever format you need. For this study, Lets use Federal Gold Medal Match (GMM) .308 175gr using yards, out to 1000y. This data is available straight out of federals catalog.

Wind Drift 10mph crosswind, GMM .308 175gr at 2600fps

| 100y | 200y | 300y | 400y | 500y | 600y | 700y | 800y | 900y | 1000y |

| 0.6 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 12.7 | 20.8 | 31.4 | 44.3 | 60.1 | 79.1 | 101.0 |

So, it becomes pretty apparent why wind estimation is so critical at long range. In the example above, if you were shooting at a target 800yards away, in a 10mph crosswind, you would hit 5 feet to the side of the target. A 10mph wind is only about enough to raise a little bit of dust. So, the next question to be asked is this, what if it is a 5 mph wind? or a 20 mph wind? or a 8 mph wind? Here is where the wind charts in 10mph are helpful. For wind effects on bullets, and for field sniping, it is close enough to say that the wind effect is directly proportional to the wind velocity. So, a 5 mph will affect the bullet half of what the 10 mph chart says. Or a 20 mph is twice as much as the value listed above. In reality, its not 100% exact, but its certainly within a few percentage points, close enough unless you are a competition shooter trying to set records. The differences are more noticeable the longer the ranges, but still close enough for our line of work. So, at 800 yards in a 5 mph wind, the bullet would drift 30". The charts being in 10 mph makes the math a little bit easier. If you estimate a 15 mph wind, then just take half of the value and add it to the number to get the adjustments. That same 800 yard shot in a 15mph wind would be 90" (half of 60 is 30, add it to the 60 to get 90) or 11.25 MOA.

There is another way besides wind charts to estimate how much the wind will affect the flight of your bullet. This is called the "Wind Formula" and it converts the adjustments you need at various ranges to MOA adjustments you can dial into your scope. Now, this is just a rule of thumb and should only be treated as such. But it can get you close enough in most cases. I do not necessarily like this formula, but others do, so I will present it here.

RANGE (Hundreds of meters) X velocity (MPH)

---------------------------------------------- = minutes (full value wind)

Constant

The constant is based on the range and is:

0-500m = 15

500-600 = 14

600-800 = 13

800-900 = 12

900-1000 = 11

So, as an example. If the target is 800meters away, and the wind is estimated at a full value of 8 mph. You get:

8 x 8

------- = 5.33 MOA

12

Which if you compare to the chart above, is just about right. Of course, this is a rule of thumb for calibers and loadings that are close to the M118LR/GMM 175gr.

So, if you know the velocity of the wind, and its constant and a direct crosswind, then its just math to make the adjustments. Simple as pie. Oh, but wait, when is the last time you have seen wind blow exactly 90 degrees to your position at a constant rate? (hum... never comes to mind). So, that brings us to the next section.

Compensating for non standard winds

Okay, so, the wind charts are all fine and dandy, but not so helpful given the fact that no wind is ever steady and blowing 90 degrees to your position. But, they are our constant that we do know, so it is what we have to work with. So how to be make them more relevant to our needs? Here is where the science turns a little more to an art, but still has a little bit of science in it.

Lets first talk about wind not being a constant velocity. Lets pretend that the wind was indeed blowing 90 degrees to our shooting path (it does happen on occasion). But, you know as well as I, that the wind is going to be changing velocity at various points and times down the shooting path. We also know that in the early parts of the bullets flight, when the velocities are highest, the wind will have less effect upon the bullet. But as we get further down range and the bullet gets slower, the wind becomes more effective and our estimations become more critical. Using this bit of knowledge, a good rule of thumb is to do your wind estimating at 2/3's of the distance to the target. This is where the wind really starts to affect the flight of the bullet. So, using your spotting scope or what ever other means of estimating wind (don't worry, estimating the wind is coming up a little further down the page) and focus about 2/3 - 3/4 of the distance to the target and estimate your range.

Now, this is only a rule of thumb. One very important thing you should do, if you have the time (perhaps when filling out your range card) is to examine the flow of the terrain. Air is very much like water. It likes to flow down hill and through canyons, etc. So while examining the terrain, you want to notice and mouths to canyons along your flight path, and generally try to pick out areas where the winds may pick up or even flow the other way. One very "cool" training exercise is to go out when its snowing with a set of optics (preferably a spotting scope) and get into the mountains or other area where you can watch the snow fall over a long range and different terrain. It is amazing to see all the different ways the snow falls because of the air/wind. This really helps you start to understand the flow of air. Where the snow is falling different directions, there will your bullet be affected also. Again, use the 2/3's rule when trying to determine which canyons to be most concerned with. If there appears to be a channel of wind both near you and further down range, you need to pay more attention to the one futher down range where it'll be affecting your bullet more. So, to make your wind calls, you will take into account all the different factors for the full length of your field of fire and make a guess trying to add or subtract for the different variations in the wind. The 2/3's rule will work in most cases, but be aware of the terrain to know when it requires a more detailed look than just estimating the wind at 2/3s the distance to the target.

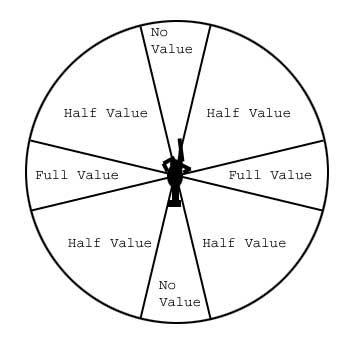

Now, lets talk about the direction of the wind. Obviously, if the wind is blowing at our back and we are shooting directly down wind, it will not affect us the same as if the wind were 90 degrees to our bullet path. One way that is taught is to use the clock method. If the wind is blowing from the 3 or 9 o'clock position, then your adjustments are full value. If it is blowing from the 12 or 6 o'clock position, then the wind is NO value. If its blowing from any other direction, then its half value. (1,2,4,5,7,8,10,11 o'clock positions). Here is a diagram.

Of course, as we talked about above, the wind direction will change based on the terrain. So use that when making your estimations.

Estimating the Wind Velocity

Well, if you are still with me up to this point, then you are still interested in this wind stuff. We've talked about the effects of wind direction, and terrain but we need to talk about guessing the velocity. There are a few guidelines, but in reality, it comes down to experience and getting out there and doing it. Here is a chart of guidelines for wind velocity.

| Noticed Effect | Velocity |

| Felt lightly on face | 0-3 mph |

| Causes Smoke to drift | 3-5 mph |

| Tree leaves in motion | 5-8 mph |

| Raises dust and lose paper | 8-12 mph |

| Small trees drift | 12-15 mph |

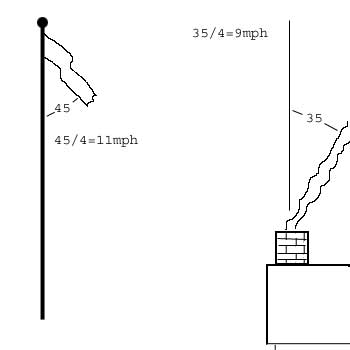

Another way to estimate wind velocity is by the range flag method, which also works for raising smoke. You estimate the angle by which the flag is being blown off of the pole, or the angle by which the smoke is drifting, and then divide it by four, that is a close estimate to the speed of the wind in MPH.

These methods are all fine, but are not going to be our primary way. As the first method is just guesstimates and is hard to get accurate, and the second method is only useful if there is smoke or flags, but is useful if there are those indicators. But our primary means of estimating wind is using our spotting scope and watching mirage. But, to be honest, there is not a good and accurate way to tell you just exactly what the mirage looks like when the there is a 8 mph quartering wind. But, I will tell you that it looks the same pretty much every time. Once you get out and practice, you can get very good at estimating wind using the mirage. When watching mirage, you need to focus on the way that the waves are shimmering. The mirage waves flow like water. The wind pushes them the same as they do the top of a lake. So it is very easy to determine what ways the waves are moving. The faster the waves are shimmering, the faster the wind is blowing. The good thing about mirage and reading it, is that it takes into account the quartering effects for you. For example, if the wind is blowing 10 mph straight into your face, the mirage will look like its just shimmering straight up. Or if it is a 10mph quartering wind, the shimmers do not move as fast as if it were blowing 90 degrees. So it helps in making your calculations.

I know that the mirage reading is vague, but there really is no way to technically explain it without just getting out there and practicing and getting used to it. After a while, you will be calling wind based off of experience and not based off of a wind chart.

One final point to mention. People in general have a tendency to underestimate the wind calls. So the phrase that is sometimes used is "Make bold adjustments". Instead of saying "Oh, it looks like about 1 MOA left", just go ahead and say "Left 3 MOA and send it". Once your confidence starts to go up, it will become more natural and you will not have to thing to make bold adjustments.

Well, there you have it... now don't be afraid of the wind, welcome it. Wind separates the true long-range marksman from the rest of the crowd. It is a challenge, but it can be tamed, perhaps never mastered, but it should not be something to be feared, because as a sniper, if you can tame the wind, and the adversary cannot, you are at a distinct advantage.